This is one of those stories where I knew of its stature for as long as I can remember but was never assigned to read it in school, and I figured during a city-recommended self-quarantine for two weeks (even though I’ve tested negative and feel fine) would be the best time to read the entire book and immediately watch this. I can clearly see why it has garnered all of the respect over the years from educators, students, writers, and some aspiring lawyers, both young and old. The standout element to me, beyond the general appeal to human decency in the face of evil, the timeless theme of loss-of-innocence, the measured spare prose describing the nightly horrors lurking underneath Maycomb’s friendly facade, and the surprisingly forward-thinking (at least given the time and place this story is set in) views on gender, class, and race, is that this makes sense as the main prestige novel to teach American students about empathy.

Time and time again, almost at the end of each chapter, Atticus stresses the importance of withholding judgment of one’s character until, say it with me, “you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.” He understands that most people, in and of themselves, do not come out of the womb hating others based on the color of their skin. Everyone is a product of the environment they were raised in, extending from the setting of Maycomb, Alabama, to the culture, religion, and family histories that inform the politics of where they are raised. Atticus believes that every person does have some good or basic decency in them, taking this to a degree where even the lowliest, wicked, racist, and possibly incestuous people that live in Maycomb all have their emotional reasons for doing what they do, and at the very least they should be considered.

That’s not an easy perspective to maintain, especially when such evil is at his doorstep or spitting in his eye. It also doesn’t mean everything is excusable, seeing as Atticus is speaking from his gut when he calls people who mistreat others based on race “trash.” It’s not any easier to hear or say in this day and age, having just come out of 4 years of the worst president of all time and still being left with his army of sycophants. But what this story does more strongly than a lot of other stories that take on this period and make it all about the white perspective is that this one is all about acknowledging the toxicity of the whites while simultaneously acknowledging the harsh conditions that would lead them to be toxic and how that hurts them as well. It’s not a story that’s interested in pointing fingers or going out of its way to make these racists seem not all that bad or worse, “very fine people on both sides.” The Ewells are the most tragic figures in the story, stuck in a cycle that’s now dragged the whole town into their shit but has ruined their family irrevocably, first and foremost. In my view, this story earns its “hurt people hurt people” perspective on empathy.

I’ve read a couple of the criticisms of both the book and the film, many of which amount to putting it in the same company as any other neoliberal white savior narratives, and while I can understand where they’re coming from, even with this being my first time with this story, I believe that there is still substance and relevance to this. I’m not just saying that simply because it doesn’t measure up when I put it against other white savior narratives, both recent and much older, though that is a factor.

The key difference here is that Atticus not only takes this case knowing damn well that he’s got a meager chance of actually saving Tom Robinson. He takes it knowing he could be caught in the crosshairs of the spiteful racism that’s been around long before he was born and will still be here long after he’s gone. He knows that the Maycomb residents won’t approve and will probably intend to hurt him and his family. He knows that the jury will still reach a guilty verdict no matter how compelling his cross-examinations and closing speech are. And he still sticks to his principles, does the hard work, and nakedly pleads to the better qualities in men, in his everyday work and everyday living, not in spite of the town’s hatred, but precisely because of it. Best of all, he didn’t do it for his own pride or out of any sense of guilt. At times, it almost doesn’t even seem like he’s doing it specifically for Tom because in Maycomb, that could have been any black man accused of rape. He did it for the sake of the future. He knew that the long journey of human progress begins with many failures of justice in order to achieve any of the major or minor successes that would make the records of history.

Having said that about him, when I read that Aaron Sorkin wrote the most recent Broadway adaptation of this with Jeff Daniels in 2018, I immediately thought, “Of course.” If what I said about The Trial of the Chicago 7 didn’t already make it clear, Sorkin’s talents for writing compelling court opera hit a political ceiling against his love of a character who is as well-spoken as he is, shares his views, and does unquestionably good deeds, getting in the way of the other voices within his stories and cheapening the dramatic function of the whole piece. But I am going off of my own prejudices built from years of watching his work, plus reviews of the performance that I’ve read from other people, so this is an incomplete opinion at best. It’s not to say anything about his bad habits taints this story or that now it sucks because he’s done it. After all, I don’t know. I haven’t seen that play, and unless it’s been recorded, I don’t know if I ever will. But on the surface, it makes sense why he would want to take on the ultimate do-gooder that is Atticus Finch.

But forgive me, I’ve gone on for several paragraphs without even mentioning how this works as a movie adaptation. Again, I did not grow up with this, so it’s probably all the more reason it’s easy for me to say this, but I thought this was just fine. Not the best film I’ve ever seen, definitely not overrated, plenty to like, but I’ve got some discrepancies that I’ll just get out of the way now;

First, this feels like watching the kind of movie where most of the director’s attention went to the performances and not much else. I know that it cost hundreds of thousands for Universal to build the backlot sets of Maycomb, but they still look like sets. I get that this takes place in the Depression, but none of the houses look like anyone is living in them; they look like sets! The editing also feels flat, mainly because many scenes end on notes of stilted silence between characters. There’s no cutting at the end of anyone’s lines. When the close-ups zoom in, I’ll be honest, I can’t tell if the effect was done at the time they were actually editing the film stock or if it’s something that came later in restorations, but either way, it kept knocking the frame out of focus or messing with the full resolution. It just didn’t look right.

The final few criticisms that I have would amount to asking why so many supporting characters who had entire chapters dedicated to their relationships with the children are given a scene or two here, but I can understand it for the usual pacing reasons. I would have liked to have seen more scenes with the children reading to the racist Mrs. Henry Lafayette Dubose until she died in the process of kicking her morphine addiction because that shit was moving, but after seeing the cheap old-lady make-up job they did on Ruth White, I can understand why most her scenes were cut, for both practical reasons and the pacing. Though while I’m still complaining, I also don’t care for most of the score in this film, but that probably is more my taste over it being wrong or anything.

Even the scene that Roger Ebert famously criticized, where the mob shows up to Tom Robinson’s cell and Scout talks to Walter Cunningham without reading the room for so long that he becomes racked with remorse, causing him and the rest of the mob to simply leave… Again, I can understand where he’s coming from when he called it a “liberal piety,” but let me purpose this; The late great Dick Gregory said once on the topic of police reform that the people who are part of the system have no reason to change themselves or it because it gives them nothing to lose by killing African-Americans and everything to lose should they ever stand up for an African-American, thus turning on the white community. “Do you hate me more than you love feeding your own children?” was the question he kept posing that stopped me in my tracks.

I don’t want to pretend to know precisely what words may have been going through Walter Cunningham’s head when Scout talked him down, but based on his original intentions when he came in and his subsequent decision to leave, it may have been something along the lines of, “Do we really want to risk making this child fatherless?” I also don’t want to pretend that’s an epiphany that occurred to many real-life white mobs before the thousands of lynchings that took place in the south. But for the sake of making the point within the scope of fiction that even in the darkest and most hate-filled places on earth, there can emerge some humanity when working people realize what they’re about risk doing to someone, I believe that Lee’s script and the adaptation here succeed in demonstrating this. Throughout the whole story, Scout has already been learning that even the most spiteful people such as (Granted this is in the book, not the film) Mrs. Dubose and Aunt Alexandra may have better intentions or a side to them that has more depth than the bigotry (And it’s not shown to be easy to accept but it is there). This scene reinforces that point. Scout is just taking control of the situation herself.

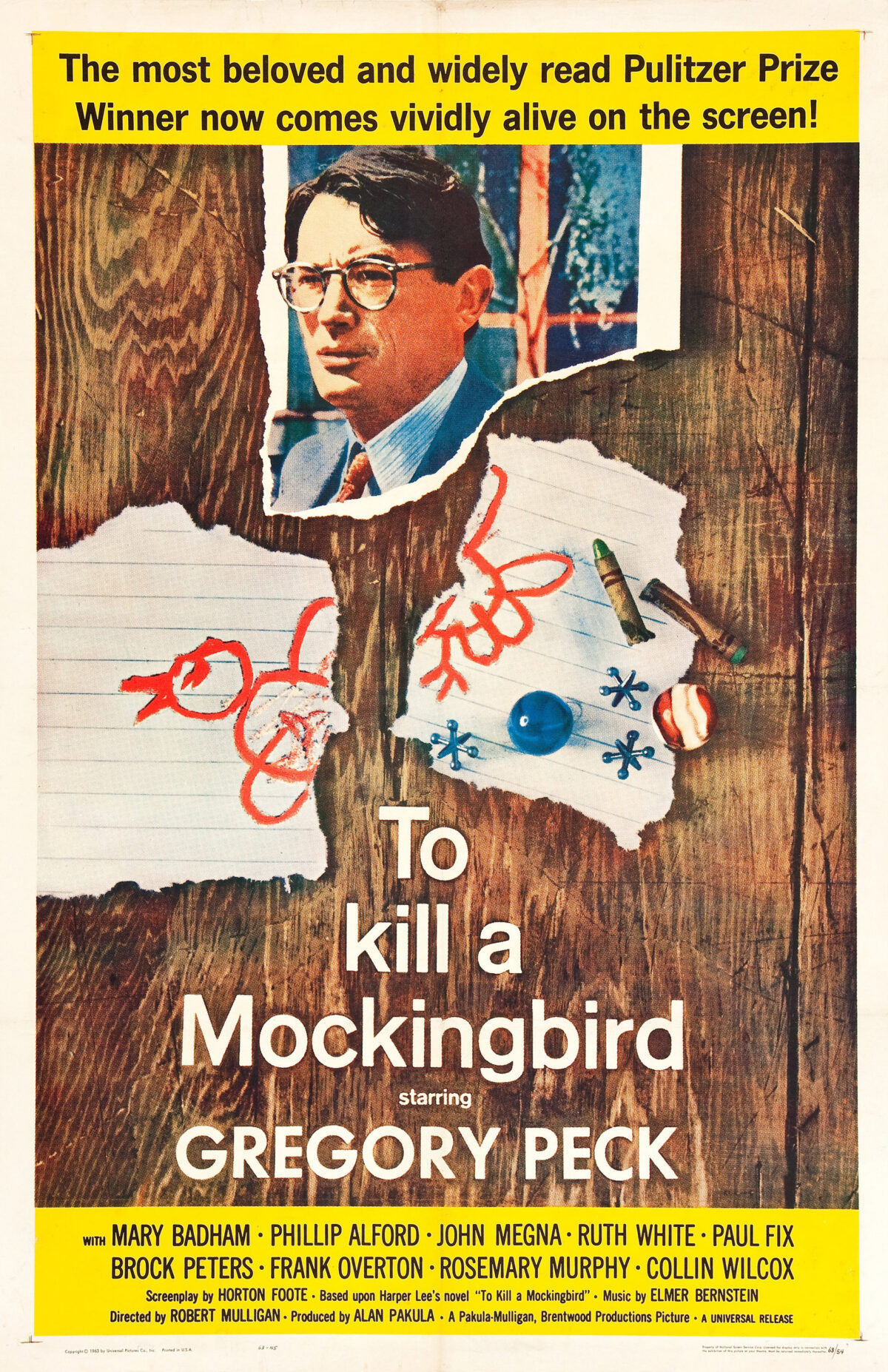

The performances are where this still shines. Even if this whole adaptation sees fit to just replicate the dialogue with some voice-over narration for a Harper Lee/Scout Finch stand-in, nobody on the cast is going on autopilot. What more can one say about Gregory Peck? This is the role he made into an instant household name. The film even gives him the entire 6 ½ minute oner courtroom speech, and it’s the only time it stops feeling like a play on a Leave it to Beaver set and actually looks and acts like a film. While reading the book, I looked forward to seeing who would play Maudie Atkinson and Rosemary Murphy is great, but I wish there was more of her in the film. The show’s real star is Mary Badham as Scout, who I can’t imagine had an easy role, having to navigate the already toxic subject matter as both a character and an actress, given what was going on in the country at the time of this film’s release. Lee’s narrator being an older woman looking back on her younger years with a wiser eye and ear for human behavior, gave the perspectives of the novel such weight. Badham pulls off an innocence that still cautiously believes in people’s basic goodness, and I’d say it’s a shame she didn’t act more, but I can respect her reasons for retiring early.

3 ½ out of 5 stars to the film adaptation and 4 out of 5 to the book. That’s about all I have to reflect on after catching up with this classic—no intentions of going anywhere near Go Set a Watchman at this time.