⭐⭐⭐⭐

Rating: 4 out of 5.A film that orbits the chilling idea of genetic segregation—a concept that, with the rapid advancement of genome splicing and gene editing, feels less like science fiction and more like an inevitable future. At its core, Gattaca presents a world fractured into two distinct castes: the “Valids,” or “Vitro’s,” genetically perfected specimens free of flaws, and the “In-Valids,” those born naturally, left to languish in the shadow of their engineered counterparts.

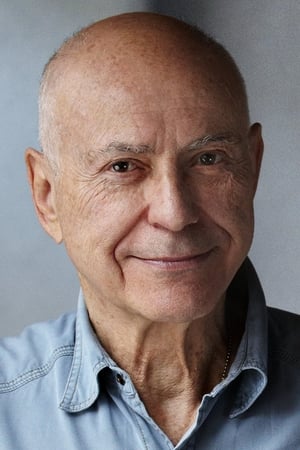

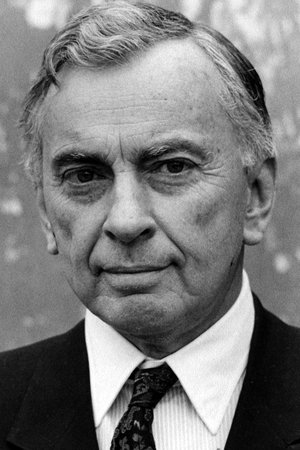

Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) is our guide through this sterile dystopia. Born of love, not design, his first breath is met with a death sentence—a heart defect that promises to claim him by thirty. The cruelty of this world is in its precision: a single drop of blood dictates his worth before he can even speak. His father, Anton (a man whose disappointment is as palpable as his pride for his second, perfect son), denies him the family name, branding him instead as “Vincent Anton”—a constant reminder of his inferiority.

Anton’s true heir, Antonio (Elias Koteas), is everything Vincent is not—genetically optimized, flawless, the ideal. The contrast between the brothers is more than physical; it’s psychological warfare. Vincent grows up in a world that tells him, in every glance and institutional barrier, that he is less. Schools won’t risk him. Employers won’t take him. Even his parents, in their quiet resignation, treat him like a liability. And yet—Vincent refuses to break. His heart may be weak, but his will is iron.

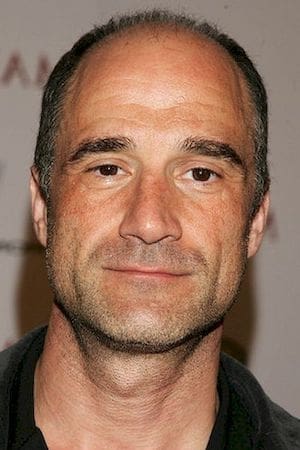

The film lingers on Vincent’s fixation with the stars, his gaze forever tilted upward. Is it love for space that drives him, or simply the need to escape a planet that has rejected him? Gattaca, the elite aerospace corporation, becomes his impossible dream—a place where only the genetically pristine may ascend. But Vincent, ever the alchemist of his own fate, refuses to accept impossibility. Enter Jerome Morrow (Jude Law, in a performance laced with bitter brilliance), a former Olympian whose golden genes are now shackled to a wheelchair after a suicide attempt. Their arrangement is a Faustian pact: Vincent borrows Jerome’s identity, and Jerome, in his self-loathing sarcasm, gets to live vicariously through a man who refuses to surrender.

The lengths Vincent goes to maintain this charade are staggering—meticulously scrubbing dead skin, injecting another man’s blood, even preserving synthetic urine samples. It’s a daily performance of deception, a ballet of paranoia and precision. And yet, the film’s most haunting question isn’t whether Vincent will succeed, but what it costs him to try. Every glance over his shoulder, every calculated movement, chips away at his sense of self. He is both liberated and imprisoned by his fraud.

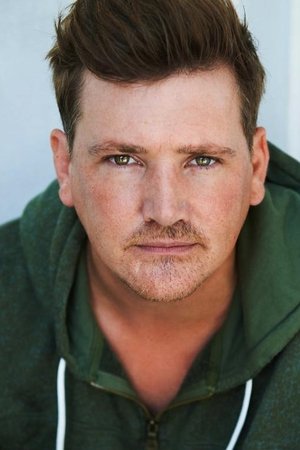

A subplot involving the murder of Gattaca’s director feels somewhat grafted onto the narrative—a necessary device to reintroduce Anton as the detective hot on Vincent’s trail, but one that disrupts the film’s otherwise hypnotic rhythm. Still, it gives way to the film’s most poignant moments: Vincent’s fragile romance with Irene (Uma Thurman) an equally “flawed” woman, who loves him before she knows the truth, and the brothers’ final, moonlit swim—a reckoning in the waves, where the question isn’t who is stronger, but what strength even means in a world that has already decided the answer.

And then—the ending. A last, cruel hurdle: a urine test Vincent cannot fake. But in a moment of grace, the doctor (who may have always known) lets him pass. Only a sympathetic speech with an acknowledgment that some dreams are worth breaking the rules for. As Vincent ascends toward the stars, the film leaves us with a quiet truth: perfection is a myth. The human spirit, flawed and relentless, cannot be quantified by a strand of DNA.

Gattaca is more than a cautionary tale. It’s a love letter to the misfits, the stubborn, the ones who claw their way forward even when the world has written them off. Because in the end, the only thing that defines us isn’t our genes—it’s the fire in our chests, the refusal to kneel. And that, no machine can predict.